As

Jesus was setting out on a journey, a man ran up,

As

Jesus was setting out on a journey, a man ran up,

knelt down before him, and asked him,

"Good teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?"

Jesus answered him, "Why do you call me good?

No one is good but God alone.

You know the commandments: You shall not kill;

you shall not commit adultery;

you shall not steal;

you shall not bear false witness;

you shall not defraud;

honor your father and your mother."

He replied and said to him,

"Teacher, all of these I have observed from my youth."

Jesus, looking at him, loved him and said to him,

"You are lacking in one thing.

Go, sell what you have, and give to the poor

and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me."

At that statement his face fell,

and he went away sad, for he had many possessions.

Jesus looked around and said to his disciples,

"How hard it is for those who have wealth

to enter the kingdom of God!"

The disciples were amazed at his words.

So Jesus again said to them in reply,

"Children, how hard it is to enter the kingdom of God!

It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle

than for one who is rich to enter the kingdom of God."

They were exceedingly astonished and said among themselves,

"Then who can be saved?"

Jesus looked at them and said,

"For human beings it is impossible, but not for God.

All things are possible for God."

Peter began to say to him,

"We have given up everything and followed you."

Jesus said, "Amen, I say to you,

there is no one who has given up house or brothers or sisters

or mother or father or children or lands

for my sake and for the sake of the gospel

who will not receive a hundred times more now in this present age:

houses and brothers and sisters

and mothers and children and lands,

with persecutions, and eternal life in the age to come."

Mark 10

Several

interesting things are happening in Sunday’s Gospel.

In

the first paragraph, Jesus encounters a man who wishes to know how he can inherit

eternal life. He asserts that he has followed the law impeccably. Jesus suggests

he needs to do two more things. The first

is to give away all that he has to the poor.

The second is to follow Jesus.

A

transactional or dualist approach to faith makes quick work of this passage: God

requires that you follow the commandments, give to the poor to improve their economic

circumstances, and finally follow Jesus’ example of going around doing kindnesses

and being humble.

Alistair

McIntyre turned moral philosophy on its head in his 1981 book, After Virtue, by

pointing out that while modern moral philosophy is almost always about making

the right moral decision in hard cases, in Aristotle’s time, moral philosophy was

about cultivating good moral habits and becoming a habitually good person. Aristotle was not particularly interested in

the moral quandaries modern moral philosophers pose for themselves. Aristotle wanted to know how to be a good,

virtuous person.

We

can be reasonably sure Jesus followed the Aristotelian model. When Jesus tells

anyone to give their money to the poor, it is never to change the economic circumstances

of the poor. Judas thought the opposite

and, after the episode with the nard, he was so scandalized by Jesus’ refusal to connect faith to altruism he betrayed him to his executioners. Jesus is advising the man how to be a whole person.

Part of being a whole person is to keep material possessions in perspective

and, for the truly committed, to cast them off entirely.

What

does it mean to follow Jesus in this context?

Almost certainly Jesus meant that this man should drop everything and literally

follow Jesus in an ascetic life. This is

a uniform prerequisite for the most dedicated spiritual pursuits in every

tradition. The Buddha, for example, named

his newborn son “Tether” and abandoned him and his wife forever in order to

lead an ascetic life. Elsewhere, Jesus and

Elijah tell prospective disciples to leave their families, leave their livelihoods,

and even leave the dead unburied to follow them. It is not a life for everyone. It is not a morally responsible choice for

everyone.

Then

Jesus offers his famous “camel through an eye of a needle” metaphor. We must

never fail to read this passage to the end. Jesus recognizes that no one is

good, no one is without sin, no one has successfully ransomed his own life or

been worthy of the divine sacrifice represented by Jesus’ incarnation and death.

This is not a threat of hell. As usual, it is a promise of salvation for

every single human being that has ever lived and an invitation to us to rejoice

in that rather than to begrudge it being given to those who we feel might not deserve it. None of us deserves it. Our human desire to commodify God’s love and deeply resent its non-exclusivity is

the point of a raft of parables and stories: the multiplication of loaves, the workers in

the vineyard, the prodigal son, Jonah, Job, the man blind from birth, the

wedding feast, and the Beatitudes to name just a few.

Read Luke 4:14-30 carefully: what causes Jesus to be nearly thrown off a cliff in his hometown is not that he declared himself the messiah; it is that he declared that people other than Jews would receive salvation! But we will always skew the interpretations

to make God’s love conditional and limited again. I believe it is that human instinct that got

Jesus crucified. Are we really Christians before we come to terms with this?

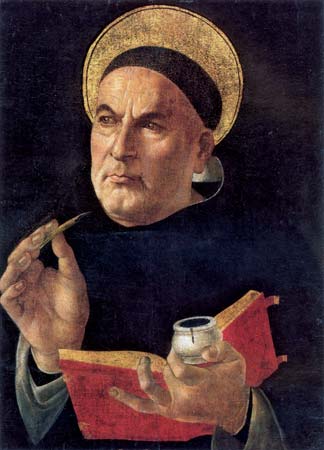

Aquinas distinguished between two kinds

of volition. First, there is the inevitable attraction to those things that you

deem perfectly good or desirable. You always will choose what you perceive as perfectly

fair, for instance. Aquinas would say you

are not truly “free” to choose otherwise.

Aquinas distinguished between two kinds

of volition. First, there is the inevitable attraction to those things that you

deem perfectly good or desirable. You always will choose what you perceive as perfectly

fair, for instance. Aquinas would say you

are not truly “free” to choose otherwise.